Berlin’s “Right to the City” Alliance succeeded in halting developments worth 3 to 5 billion euro

By Barbara Matejčić

Croatian version

Despite the snow falling thickly and unceasingly on a freezing Monday late last year, a now fancy café in Friedrichshain, a one-time East Berlin working-class district, was packed. In a completely ordinary café, usually closed Mondays, mostly middle-aged people gathered around to hear what architect and activist Carsten Joost had to say. Carsten Joost could very well be described as Mediaspree Versenken’s (“Sink the Mediaspree”) poster-boy; namely, Mediaspree Versenken (“Sink the Mediaspree”) is a Berlin urban initiative that articulates Berlin’s inhabitants’ contemplations and requests in view of spatial politics, investment projects including developments and changes in the city’s tissue in general. To simplify things we could state that the Mediaspree Versenken is the Berlin “Right to the City” Alliance, as their goals and methods are quite similar, while the capital at stake is incomparably higher as is the pressure investors are putting on the city’s authorities.

The Mediaspree Versenken regularly hold meetings on Mondays, informing their steady supporters on what’s new and jointly plan future activities or acquaint new members with their work, as was the case this particular Monday. Collaboration with citizens and information on what’s happening in town is one of their main activities. The other being negotiating and applying pressure on investors and city authorities. This time Joosta invited the café’s owner. After bringing him up to date on the initiative’s five-year-long work and activities a discussion ensued. The visitors for the most part condone Joost’s activities, some propose new actions, some hold that they’re not combative enough, others that their fight is useless as Berlin is up to its neck in debt as it is and city authorities desperately need investments and won’t be willing to negotiate with citizens… It’s precisely this money crunch – namely, Berlin’s bankruptcy and its €60 billion debt – that prompted its opponents to align themselves into this initiative expressing strong dissent in view of Berlin’s largest ongoing development project. As it turns out that the city authorities are actually quite alert to citizens’ thoughts on the matter. However, only after the citizens coerced them into listening-mode.

Here’s how the story goes: following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the derelict districts of Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg, located along the Spree River, found themselves in the center of the city. Friedrichshain was on the east side of the Wall, while Kreuzberg was on the west, and the districts were mostly inhabited by poverty-stricken residents. The West Government appointed low rents for that area to attract residents, so immigrants lived there for the most part, and as early as 2006, 31.6% of residents didn’t have German citizenship. Not even the river bank, where industrial and warehouse facilities were once located, was really developed after a good part was laid to waste during the Second World War. In time, various more or less temporary ways of using the remaining derelict industrial premises dating back to the 19th and 20th century started developing – these premises were populated by the alternative cultural scene, restaurants and catering facilities, etc. Parallel with that, the city management started to develop the “urban development” project of that area which became extremely significant following the Wall’s fall. That was in line with the former Berlin Minister’s, an SDP politician and economist Thil Sarrazin’s “clearance sale policy”. Thil Sarrazin is the same politician whose last year’s claim to fame was a book he published (and the term “claim to fame” isn’t necessarily meant as an ironic remark as his book got him a lot of followers), the book “Germany Does Away With Itself” being an ode to racism, where he warns about the perceived threat that uneducated, unemployed and unintegrated mostly Muslim immigrants are detrimental to Germany’s advancement. Even before his controversial book was out, Sarrazin wasn’t popular in Berlin, the city he lives in, because he called out its inhabitants as being lazy and unmotivated for work, for which he blamed the city’s various state subsidization policies. His theory was that real estate in the city’s ownership is the very place where the greatest potential lies for economic exploitation as well as for plugging gaps in the city budget. This idea of massive privatization has obviously taken hold along the Spree River area.

The project was mainly designed so as to sell the land which was the city’s property and soon came to be known as Mediaspree, as it was intended to situate a good deal of media and telecommunications industry here – e.g. MTV, Viva, and Universal Music headquarters. They advertised their project precisely with such pop-cultural references – “We want to attract young and attractive residents who watch MTV and can be defined as ‘sexy.’” This kind of marketing strategy didn’t go over well in a neighborhood where students, artists, squatters, punkers and immigrants reside, regardless of the fact that during the past twenty years the structure of the residents shifted according to how the neighborhoods were arranged.

The project covers an area of 180 hectares (445 acres) sprawling along a length of 3.7 kilometers (about 2.3 miles) along both river banks. This huge surface area is divided into more than 50 parcels. Various developments are set to be placed here – large companies’ headquarters, residential buildings, office spaces… the investment is estimated at a total between €3 and 5 billion. The investment in question is one of the biggest investment projects in Berlin since the fall of the Wall where competition has been tough. Mediaspree is neither an investor nor corporation, but actually a sort of brand of the project that gathers various larger or smaller investors, landowners, construction companies and functions as an “info center” for various interest groups involved in the project while at the same time lobbying with authorities for the project and its image so as to get citizens on their side. It went quite easy with the city authorities, despite their being a coalition of social democrats and the Left-wing party, stemming from the former East German communist party, so one would expect they’d be socially sensitized and aware. However, both were very clear: investments are a necessity. Thus the leftist citizens found themselves at odds with precisely those they brought to power. The politician’s main argument is the numerous work opportunities the Mediaspree would bring, speculating on 20 to 40 thousand new job vacancies. The project was proclaimed a public private partnership, by a recipe we are quite familiar with: private development and private profit, with public funding for infrastructure financing – streets, bridges, lighting… however, it didn’t go down so well with the citizens.

Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg residents quickly concluded that the Mediaspree realization will change their neighborhoods bringing with it new “sexy” neighbors, in turn causing rent to go up once capital starts seeping into their neighborhood forcing many to find cheaper places to live. Precisely what had happened in other Berlin neighborhoods that underwent a so-called revitalization, i.e. gentrification. When the project was presented they understood that the former public space would be privatized, as dense and high-rise developments are planned, and a mere 10 meters (33 feet) from the river at that. They started to self-organize in 2006 when the first meeting was organized by the members of the LGBT community. Then the Mediaspree Versenken initiative came about, where in time Carsten Joost “imposed” himself as the leader of the resistance project.

After obtaining his architecture degree in Frankfurt am Main, Joost worked in Albert Speer Jr.’s office (yes, the son of Hitler’s main architect) and then after more than a decade moved to Berlin. He occasionally works in his profession, but for the most part volunteers in various citizens’ initiatives directed at urban planning. For example, he made an effort for the Palast der Republik, a seventies building where the former GDR Parliament was situated alongside various cultural programs, to become a place of different cultural practices, but it was nevertheless torn down in the end. In regard to his years-long engagement with Mediaspree Vesenken, he says, he charges no fee whatsoever. In addition to various activities and actions they have carried out so far (e.g. organized the first Berlin protests in the Spree River, when they floated on various plastic props thus preventing the ship’s passage where Mediaspree representatives presented their project to potential investors) their biggest success up to date was when they collected a sufficient number of votes from the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district residents to obtain the right of holding a referendum. They had but four weeks until the referendum, and they used that time to inform citizens which in turn resulted in a whopping 87 percent of voters declaring themselves against and voting anti-Mediaspree. As Mediaspree Versenken isn’t against development in general but rather against construction that’s so close to the river (they request a minimum of 50 meters /164 feet/ of a free zone along the river), they’re against development of skyscrapers (buildings taller than a 100 meters /328 feet/ were planned while their request is that the cut-off height should be 22 meters /72 feet/, which is the standard permitted height in Berlin anyway) as well as against the development of a traffic bridge over the river (they want the bridge to be open only to pedestrians and cyclers). Those requests were part of the vox populi questions.

“From protest organization to program proposal” is one way of summing their work up. Their main goal is that the river bank be available to everyone. The problem lies within the fact that a good part of the land has already been sold and it’s been estimated that it would cost the city approximately €165 million to repurchase those additional 40 meters (131 feet) of river bank land. However, the referendum and the subsequent financial crisis, brought both construction and further land-selling to a halt, and due to a negative public image, the investors stopped presenting themselves under the Mediaspree “label”. While prior to the referendum, nobody, especially the investors, was interested in the citizens’ opinions, they are now impelled to take them into consideration. Some of them dubbed Joost a “bonsai demagogue”, a communist dreamer and a misguided Robin Hood, while other investors still consult with him in view of what to do to avoid the citizens’ rage. Joost negotiates with everyone who feels up to it, his option is moderate, one could even say pragmatic. He himself says that he deals with reality not fantasy. That means he’s aware that such a huge project can’t be completely deterred, but can be modified to force the government to consent to their conditions. Instead of being a mere citizen opposition to the government and investors, they are trying to impose themselves as the public-interest keepers ready to participate in the decision-making process.

Mediaspree Versenken is one of several initiatives directed against Medaspree. They have the same goal, but their methods differ. The most radical among them are the Spree pirates – who are supported by the Black Block – and they refuse to negotiate with anyone who is within the power structure, only addressing the media and citizens, while Carl Joost is ready for talks with both investors and politicians and his initiative has the largest number of citizens. He tends to the poorest citizens first, as he holds that the others will somehow manage to cut a deal with the companies, while there’s nobody to look after the immigrants.

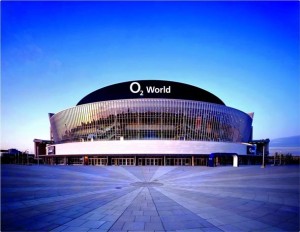

The whole project is currently in a rest period. Following the construction of the O2 World Arena, the realization of the plans came to a halt although when the Arena was built in 2008, it seemed as if the battle of who reins the city was won – profit interests over the citizens. The construction of the sports hall for 17.000 visitors was accompanied by a lot of controversy and citizens’ protests culminating in the preposterous decision to remove 45 meters (147 feet) of the Berlin Wall for a big screen announcing events in the Arena. Namely, the Arena was built near the preserved 1.3-kilometer (0.8 mile) long area of the Wall along the Spree River, which artists have been painting since 1990 and which has become known as the East Side Gallery, the longest open air gallery in the world. Although the East Side Gallery is protected as a historical monument, as much as 45 meters (147 feet) of Wall was nevertheless removed so the Arena’s display could be viewed from the other side of the river and so ships with visitors could dock there. The Arena became a symbol of inhumane urban planning to the citizens, while the local newspapers dubbed it “the nameless Arena” and a “UFO” because its architects’ names remain unknown, highly unusual for a city obsessed with architecture. The Arena confirmed that the profit growth rate overpowers all other arguments and rights, which doesn’t mean that the battle is completely lost as yet.

Nikolaus Bernau is an architect and publicist who edits the urban planning and architecture section in Berlin daily the Berliner Zeitung. We talked in a fancy health-food diner, one of many in Prenzlauer Berg, a neighborhood unrecognizable now as opposed to twenty years ago and which is often used as an example of gentrification. You can clearly see here how capitalism functions as a system organized by society and how right David Harvey is when he says that the quality of urban life has become a commodity for those who have money. The most recent research reveals that from 1991 to 2003 75 percent of inhabitants moved out of the former East Berlin “blue collar” neighborhood. A fluctuation of 30.000 people per annum, who either moved in or out of Prenzlauer Berg, has completely changed the social image of the place. Today 85 percent of the inhabitants are 18 to 45-year-olds. Mainly educated singles, couples without children or with toddlers. It’s virtually impossible to bump into older people or members of a lower socio-economic class on the street. Should the plans be realized, the Prenzlauer Berg effect could very well spread to the Spree river bank.

Nikolaus is a priori neither for nor against the investment projects. Aware that behind neatly arranged facades hides a city in endless debt, a high unemployment rate, subsidized only by financial shots from the national budget, and that development is always a good economic impetus. However, on the other hand, he reflects, Berlin had a population of 4.5 million in 1939 and was planned for six million, while it currently has a population of 3.4 million which is decreasing annually. In addition, during the nineties billions of euros were invested into new developments, resulting with a lot of empty space (it’s been estimated that Berlin has around 100.000 empty apartments) and Nikolaus wonders whom these Mediaspree project apartments and office spaces are intended for. In addition to that, he considers the whole plan un-ecological, architecturally non-inventive, an excessively close line-up of residential and office blocks with a lack of green and public spaces. Not even the German Architectural Center had anything positive to say about Mediaspree: they released an official announcement stating that although it’s an excellent location that citizens should be offered something more interesting than yet another project oriented solely towards the investor’s interests.

And there we have the profession’s opinion. At the same time, Carsten Joost is convinced that the investors will have to consent to a compromise. The investors are however sending word that their project is a priority of “substantial political significance to the city” while the referendum was but a mere expression of “citizens’ opinions”. The council of the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district is somewhere in the middle, forming a committee with representatives of all interested parties – the investors, city authorities, citizens and the profession itself. If all goes well, the final decision rests with them.